Why does ridesharing freak out some regulators?

THE RIDESHARING DEBATE: Regulators across the country are debating whether to treat ridesharing companies like Lyft and Uber the same as taxi cabs.

By Rob Nikolewski │ New Mexico Watchdog

Economist Matthew Mitchell says ridesharing companies make a lot of sense in places like Albuquerque, N.M., where he was born and grew up.

“There’s limited public transportation there and there are a bunch of drunk 20-year-olds on a typical Friday and Saturday night,” he says with a laugh.

But opponents, including regulators in various locales across the nation, aren’t laughing at all.

They insist companies like Uber, Sidecar and Lyft must abide by the same rules as taxi cab companies and, in some cases, they’re cracking down hard on the startups that use smartphone apps to attract passengers.

Case in point: The City Council in Washington, D.C., not only wanted to heavily regulate ridesharing companies, but proposed making them charge no less than five times what D.C. cab companies charge their customers.

So a $20 fare in a cab would cost a passenger using a ridesharing company at least $100?

“That’s right,” said Mitchell, senior research fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University. “But these companies alerted their tech-savvy customers and within 24 hours, these tech-savvy customers inundated the City Council with about 20,000 complaints. City Council has never had that kind of reaction from anything they’ve ever proposed, and they withdrew their proposal.”

There are other examples.

- Outside the D.C. Beltway, the state of Virginia’s Department of Motor Vehicles fined Uber and Lyft for not having “proper operating authority” to do business in the state.

- Even in the tech-friendly and eco-friendly mecca of Austin, Texas, the city impounded two Lyft cars from the tony Four Seasons hotel and cited the drivers for not having valid chauffer’s licenses.

- In San Francisco, the California Public Utilities Commission says Lyft and Uber can’t take passengers to the airport unless they have permits.

Why the hard line?

“For some (regulators), they see this as a rule of law issue,” Mitchell said. “They say, hey, this is what the law says, we can’t just ignore the the law.”

But, Mitchell said, there’s something else at play — the concept of what public-choice economists call “regulatory capture.”

“It’s the idea that over time, regulatory bodies often end up seeing the world in much the same way as the industries they are regulating,” Mitchell said. “It doesn’t always have to be a nefarious (situation) where the taxi cab companies buy them off. Sometimes it’s just, well, the people you end up interacting with the most are the folks you’re regulating.”

In New Mexico, the Public Regulation Commission is wrestling over what to do as Uber and Lyft break into the Albuquerque market.

On one hand, the PRC has locked horns with Uber and Lyft — and even issued a cease and desist order against Lyft. There’s also been talk of using the New Mexico Department of Public Safety to enforce sanctions, including potential fines up to $10,000 per vi0lation.

On the other hand, the commission also islooking at carving out new rules to allow ridesharing companies to operate in the state.

The PRC’s five commissioners appear divided.

“It’s a new, innovative idea,” said Commissioner Pat Lyons, “Let’s see how it works.”

But Commissioner Valerie Espinoza said ridesharing companies are no different than taxi cabs, limousines and van services.

“I’m all for competition,” she told New Mexico Watchdog, “but our first concern should be with public safety or it’s going to be a free-for-all.”

YOU CAN STILL CATCH A RIDE: Despite opposition from the New Mexico Public Regulation Commission, two popular ride-sharing services are still operating in Albuquerque.

Neither Lyft nor Uber have received licenses from the PRC, but both companies are operating in Albuquerque. Lyft officials say drivers are taking “donations” when they pick up customers.

“If they want to operate legal, I welcome them,” said Commissioner Ben Hall. “But if you don’t want to operate legal, we don’t want you in our state.”

Ridesharing companies insist they’re entirely different than cab companies.

“Trying to regulate a ridesharing service like Lyft as if it were a taxi service is trying to put a square peg into a round hole,” Lyft spokeswoman Katie Dally said from the company’s headquarters in San Francisco.

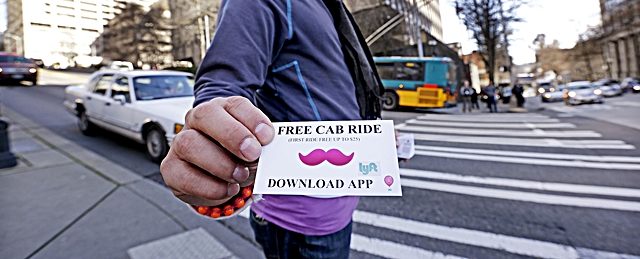

Unlike hailing a cab from the street or calling a limo service and setting up an appointment, ridesharing companies work strictly through the free smartphone apps they offer to customers.

The app allows potential passengers to find the location of nearby drivers, track the length of the trip in distance and time and calculate the cost of a ride. Since the app transfers the fee from the user’s credit card, no cash changes hands.

The drivers are independent contractors and set their own work hours. The companies get paid by getting a percentage of the fares. Lyft, for example, makes 20 percent per transaction.

But cab companies say these are all distinctions without a difference.

“They’re taking people from Point A to Point B and charging them a fare,” said Raymond Sanchez, the former New Mexico speaker of the House, who is an attorney for Yellow Cab Co. of Albuquerque and a regular presence at PRC meetings where the ridesharing debate has gone on for more than two months. “They’re operating illegally. Go by the same rules everybody else is going by.”

One of the PRC lawyers last week cited a report of a ridesharing driver charged with assaulting a passenger in Washington, D.C.

“People are riding at their own risk,” Espinoza said. “The state has a responsibility to protect people.”

The ridesharing companies say their drivers all go through background checks and carry insurance. Lyft drivers carry $1 million primary liability policies, said spokeswoman Chelsea Wilson.

Ridesharing fans accuse critics of simply trying to block out competition and innovation.

“If taxis aren’t competitive with Lyft and Uber, then the obvious thing to do is reform regulations to help them compete, not to force Lyft and Uber to adhere to onerous regulations,” said Paul Gessing, president of the Rio Grande Foundation, a free-market think tank based in Albuquerque.

While ridesharing companies have been stiff-armed in some locales, they’re getting the green light in others. In the past month, the city of Seattle and the state of Colorado each passed rules allowing the companies to pick up passengers who often employ the companies’ high-tech rating system to instantly evaluate their experiences.

“You’re far from flying blind,” Mitchell said. “You’ll be able to ask 10,000 customers who rated a driver. If you don’t like what you see, you cancel it.”

In essence, the customers become the regulators.

“What they’ve managed to do with this rating system,” Mitchell said, “is provide a regulatory quality assurance that accomplishes what reams and reams regulations and 80 years of state regulations have never been able to achieve.”

Contact Rob Nikolewski at rnikolewski@watchdog.org and follow him on Twitter @robnikolewski