Should government rules have to make sense? Texas argues no in eyebrows case

By Jon Cassidy | Watchdog.org

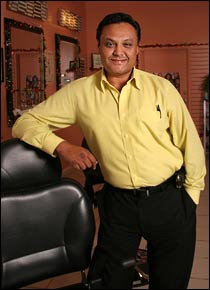

FIGHTER: Ash Patel sued to stop the state from forcing him to comply with random requirements that have nothing to do with the business of eyebrow threading.

HOUSTON – Some 99 years ago, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the idea that the right to work for a living “is of the very essence of the personal freedom and opportunity” that the Constitution is meant to secure.

Yet since then, the courts have generally granted the federal and state legislatures boundless authority to interfere with that right, even when their interference proves senseless and fatal.

I don’t mean just fatal to a business, in the common figurative sense. I mean it literally.

A Louisiana florist named Sandy Meadows died alone and in poverty after the Louisiana Horticulture Commission refused to allow her to practice the only craft she knew. A federal judge upheld Louisiana’s floristry licensing scheme, which is nothing but a racket meant to protect established interests from competitors such as Meadows, on the wholly speculative grounds that licensing might protect customers from infected dirt or sharp wires.

The Institute for Justice, a nonprofit that’s dedicated to persuading the courts to curtail extreme over-regulation, took up Meadows’ case and lost. But lawyers from the group went before the Texas Supreme Court on Thursday to argue in favor of a clear standard that would allow lower state courts to overturn particularly awful decisions by regulatory bodies and the Legislature.

The problem, they say, is that courts are so deferential to the other branches of government that even the most blatantly mindless and abusive regulations are upheld as legitimate exercises of government authority.

They picked a great case to make their point.

Ash Patel is a Houston entrepreneur who once planned to open a chain of beauty salons specializing in eyebrow threading, an ancient hair removal practice that employs taut threads to shape eyebrows. He had opened just one of the salons when he found that state regulators were requiring threaders to have cosmetology licenses. So he sued.

To get a license, you have to spend upward of $20,000 and spend a year taking 750 hours of instruction at cosmetology school, even though cosmetology schools aren’t required to teach eyebrow threading and the licensing exam doesn’t test eyebrow threading.

According to Wesley Hottot, a lawyer with the the Institute for Justice, only five of the 389 cosmetology schools in the state even mention eyebrow threading, and four of those just briefly. The coursework is largely determined by the state, which, for example, set a minimum of 100 hours of work on shampooing.

Now, if anything symbolizes the disconnect between real life and government regulation, it’s got to be those 100 hours on shampooing. A practice that most of us learned off the side of the bottle – lather, rinse, repeat – becomes some obscure technique requiring endless training.

“By comparison,” Hottot writes, “the Texas Department of State Health Services requires emergency medical technicians and paramedics to attend a 140-hour basic course followed by 624 hours of on-the-job training, and the Texas Commission on Law Enforcement requires first-time peace officers to undergo just 643 hours of training, only 16 hours of which is devoted to emergency medical assistance. … The result is that the state will certify someone to intervene in a life-threatening emergency with just 14 more hours of training than the state requires for basic sanitation in a salon. In the case of a police officer, the state believes it takes 700 fewer hours to learn emergency medical assistance than it does to learn to wash your hands and clean up after salon customers.”

Aside from hundreds of pages of legalistic arguments, the state’s case rests on a simple rationale: It has a responsibility to promote sanitation. And Hottot agrees, but he points out that salons already are covered by sanitation regulations, and that experts say that “threaders need about one hour of sanitation training to master three essential principles: wash your hands, use new thread, and keep your work area clean.”

As a matter of common sense, the state’s regulations are beyond overkill, but is that enough to make them illegal?

In theory, laws that infringe on economic liberty must have a “rational basis” to be legitimate. But federal courts have interpreted that as meaning that any conceivable justification for a law is good enough, and there’s always a conceivable justification.

The Texas Supreme Court should restore a higher standard, Hottot argues, and declare that “all laws must, at a minimum, have a ‘real and substantial’ connection … to a legitimate government interest.”

Now, that may just turn out to be some legalese that changes nothing. But I think there would be a shift in emphasis that could change everything. If you want a court to strike down a regulation now, you generally have to prove that there is no conceivable “rational basis” for it, and that means proving a negative, which is close to impossible.

But “real and substantial” shifts the burden; it would be the government that would have to prove the existence of something “real and substantial” served by its rules.

And in these sorts of cases, that can be impossible. In one brief, the state lawyer handling the case keeps coming back to a trope of his – that there is “a very real public health concern” served by cosmetology licensing, as if by insisting that something is very real he can make it so.

Like a hack magician calling attention to his perfectly ordinary deck of cards, he reveals that it’s anything but. Four times, he mentions the “very real” public health concerns, which are supposedly “described in detail above.”

But they’re not described, above or elsewhere, because they’re not real. Instead, he has to argue in the broadest of generalities, that the regulations are “rationally related to a legitimate public interest, namely, public health and safety.”

For decades now, conservatives have been complaining about “activist judges,” usually thinking of the latest high-profile social issue that went against them in court. In truth, the courts have stepped aside as the other branches of government have asserted near total authority over our business. The result is plenty of tyranny of the majority, and a slashed and tattered Bill of Rights.

The Supreme Court hasn’t overturned a regulation on these grounds of economic freedom and due process since 1937, according to one of the briefs in the case.

The Code of Federal Regulations, meanwhile, has grown from 30,000 rules in 1979 to more than 180,000 rules. Two in five workers now need, or will eventually need, government certification to do their jobs, according to one recent study, up from 5 percent in the 1950s.

If Texas wants to avoid that same sort of regulatory creep, it’s going to need a judiciary with some pruning shears, willing to snip off rules that just don’t make any sense.

Contact Jon Cassidy at jon@watchdog.org or @jpcassidy000. If you would like to send him documents or messages anonymously, download the Tor browser and go to our SecureDrop submission page: http://5bygo7e2rpnrh5vo.onion

The post Should government rules have to make sense? Texas argues no in eyebrows case appeared first on Watchdog.org.