North Dakota Is One Of The Worst States In The Nation For Civil Asset Forfeiture

In a nutshell, it’s a process by which the police can take your stuff – your money, your cars, your home, etc. – and make it their own with your only recourse typically being a legal process in which your property is guilty until proven innocent. The video above from the Institute for Justice is a good place to start if you’re just tuning into the issue.

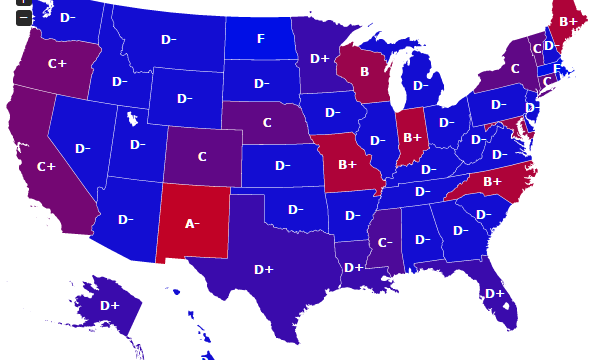

So, how bad a problem is it in North Dakota? According to a recent report put out by the Institute for Justice, North Dakota tied with Massachusetts for the lowest grade in the nation when it comes to our policies governing civil asset forfeiture.

“Along with Massachusetts, North Dakota has the worst civil forfeiture laws in the country, scoring an F,” the IJ report states.

In North Dakota, law enforcement only needs to meet the lowest possible standard of proof—probable cause—to forfeit property. And when property has been used for illegal activity without the owner’s knowledge, the burden is on the owner to prove her innocence in order to recover it. Finally, North Dakota law enforcement agents operate under a particularly dangerous financial incentive: Agencies receive up to 100 percent of forfeiture proceeds up to $200,000. If the government’s forfeiture fund exceeds $200,000 over any two-year budget period, the excess must be deposited in the general fund—encouraging law enforcement agencies to adopt a use-it-or-lose-it mentality.

What’s more, there is no state requirement that law enforcement agencies report what they take through this process. The data is available via open records request, but you’d have to make a request of every agency in the state to get a clear picture of the dollar amounts, and often the forfeiture proceeds are shared among multiple agencies.

Here’s an example from 2013 of a North Dakota man named Adam Bush who was acquitted of having stolen a safe full of cash in Hankinson but still saw the cops take his car away because, despite his acquittal, there was still supposedly probable cause to believe it had been used in a crime:

Their theory was that he took a large safe from the bar, pulled it over to a kayak, floated the kayak to his car and drove away with the safe. There were no witnesses, and according to a local radio station, even the state’s attorney admitted the case was “highly circumstantial”. A jury acquitted Mr Bush in April. His car, however, was not so lucky. A judge ruled that despite the acquittal, county sheriffs were entitled to keep Mr Bush’s car, which was seized when he was arrested.

It’s hard to imagine how you can justify taking Mr. Bush’s car because it was supposedly used in a crime he was acquitted of.

In 2014 I requested details from the Attorney General’s office for forfeiture revenues going to the state Bureau of Criminal Investigations. From the beginning of 2009 through July 23, 2014, the BCI had taken in over $341,000 worth of revenues from forfeitures.

“The assets were forfeited upon order of the court and were either ordered forfeited directly to the BCI/task force or the court ordered the assets forfeited to another law enforcement agency and because we assisted in the investigation of a case or cases, that law enforcement agency then turned over to us a prorated share of the forfeited asset funds it received,” AG spokeswoman Liz Brocker told me in an email.

That’s a lot of money. Now imagine how much it would add up to if we started taking into account every sheriff’s department and municipal police department in the state.

One bright spot for this in North Dakota is that the state doesn’t seem to be cashing in on “federal equitable sharing” of forfeiture revenues.

“North Dakota has made such little use of the Department of Justice’s equitable sharing program that the only state with a better track record is its neighbor South Dakota,” the IJ report states.

So there’s that, I guess.

Even so, if even one person has their property taken and sold for the profit of law enforcement without actually being convicted of a crime it’s too much.

This is an area of law the Legislature should address.