James Kerian: North Dakota Showcases The Power Of Competition

North Dakota’s elected officials like to take credit for our state’s booming economy. Their challengers like to point out that no incumbent every put oil in the ground. Some of North Dakota’s policy makers say that if other states did things our way the country would be in much better shape economically. Others retort that North Dakota’s policies didn’t create the commodity boom from which the state has benefited.

Regardless of the merits of these claims there is a lesson to be learned from North Dakota’s economic success that can and should be applied in all fifty states. The lesson (which comes most sharply into focus when you contrast North Dakota with the rest of the country) is that the only way to help the middle/lower/working class is to increase the demand for labor.

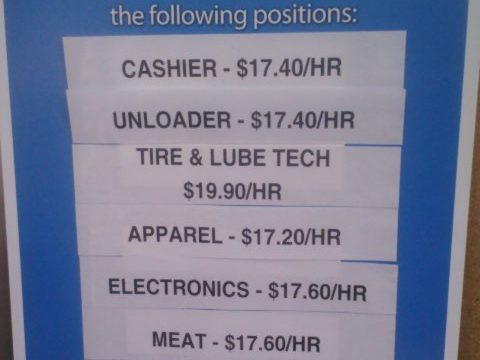

There should be no denying the increased prosperity of North Dakota’s employees whether it is judged by the census bureau or by anecdotes. This increase in prosperity has not come from a higher mandated minimum wage, a more redistributive tax scheme or an expanded set of entitlement programs. It has been solely the result of an increase in the ratio of employers seeking to hire compared to the number of employees seeking to be hired. Even with all of the people coming to this state to find work the number of available jobs has continued to outpace the number of job seekers and, consequently, wages have risen.

Employers behave strikingly similar to everyone else in the country when it comes to how they spend their money. They pay what they have to (and no more) in order to get the labor they are seeking. This may sound greedy but it is the same way you handle your money. If you drive from North Dakota to Texas you will (according to AAA) start out paying $3.45/gallon for gasoline and you will end up paying $3.27/gallon in Texas. When you get to Texas you will not walk up to a gas station owner and offer to pay $3.45/gallon just because that is what you were paying in North Dakota. In both North Dakota and Texas you will pay what you have to in order to get the gallon of gas (because the gas is worth more to you than the money) but you will not pay more than you have to. Some people will pay extra for premium gasoline and some employers will pay higher wages for premium labor but no one pays more just to pay more. That’s not greed it’s just common sense.

While North Dakota has seen wages rise in a tightening labor market the rest of the country has tried every other conceivable approach to pushing a larger percentage of wealth down to employees and the results of these efforts have been abysmal. In 2007 the Democrats pushed through congress the “Fair Minimum Wage Act” to increase the minimum wage nearly 50%. In 2009 the Democrats instituted the “Making Work Pay” tax credit to make federal income taxes even more redistributive. Of course, also in 2009, the Democrats introduced us to “The Affordable Care Act” to subsidize health insurance premiums for low and middle income households. Call it the law of unintended consequences or simply call it the law of supply and demand but these initiatives have not met with much success. Since 2007 the median household income has consistently either fallen or remained stagnant each year and income inequality is at a record high.

All of this information may appear very discouraging and not particularly useful to those who want to help low/middle income households. If redistributive taxes, minimum wage laws, and expanded entitlements are ineffective/counterproductive and the only demonstrated remedy is the tightening of the labor market that results from a commodity boom in an economy like North Dakota’s then should policy makers in the rest of the country just give up and hope for someone to find oil in their state? No, there is no reason to believe that a commodity boom is the only thing that can increase the ratio of would-be-employers to would-be-employees.

Policy makers who are genuinely interested in helping low/middle income Americans should be asking themselves what policies will make current employers expand their payroll and, even more importantly, what policies will make potential employers take the leap and make the switch from employee to employer.

Why (if restaurant profits are so high and the pay for restaurant workers is so low and interest rates are so low) are so few people interested in taking out a loan and starting a restaurant? Why (if retailer profits are so high and pay for retail employees is so low and interest rates are so low) are so few people interested in taking out a loan and starting a retail store? Why (if insurance company profits are so high and pay for insurance employees isn’t that high and interests rates are so low) are so few people interested in taking out a loan and starting an insurance company?

These are the questions that policy makers should be wrestling with at a time when corporate profits are at an all time high but new business startups are at an all time low. These are the questions that must be addressed by anyone who is opposed to income inequality or interested in helping low/middle income Americans. Because there has never been a regulation, a handout or a bureaucracy that could help low/middle income employees as well as competition between employers for their labor.