Audit coming as Pittsburgh’s pension liabilities surge

By Rachel Martin | Watchdog.org

PITTSBURGH — The Steel City will soon undergo extra scrutiny as the state auditor general examines Pittsburgh’s public pension plans. This comes after a summer report shows a slide in earlier progress made by the city.

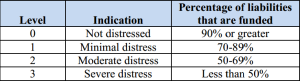

An August rundown by the Public Employee Retirement Commission shows Pittsburgh’s public pensions are funded at 58 percent, down from 62 percent in a 2012 snapshot. Pittsburgh’s pensions are still within the “moderately distressed” category.

DISTRESS DEFINITIONS: This chart, from a 2014 report by the Auditor General’s office, shows the distinct distress levels for municipal pensions. Pittsburgh’s remain in “moderate distress.”

The current funding ratio is still markedly higher than the barrel-bottom rate of 28 percent seen in 2008.

It’s estimated Pittsburgh has $485 million in unfunded pension liabilities, out of the total estimated $1.2 billion pension debt. That means many of the promised obligations to current and future retirees aren’t budgeted.

Part of the blame lies with unrealistic discount rates, the assumed rate of return for investments of pension funds. By using unrealistic expected rates of return, the amount Pittsburgh needed to contribute appeared smaller, and the city contributed less.

During the 1990s, the city used a 10 percent discount rate, said James McAneny, executive director of PERC. Those high levels of expected return were never realized, and the plans lost 40 percent of their value within a decade.

Even after that, former mayor Luke Ravenstahl’s administration insisted on not using a rate below 8 percent — with the same results.

McAneny said that as Ravenstahl was leaving office, he knocked the assumed rate of return down to 7.5 percent. This created an instant increase in the unfunded liability. While this makes things more difficult for the current administration, it’s the wise thing to do, McAneny said.

Auditor General Eugene DePasquale announced at a Nov. 5 press conference his office would conduct a regularly scheduled audit of the city’s police, fire and municipal employee pension plans.

Though the plans are in distress, they are “not yet in a free fall and we want to keep it that way,” DePasquale said in a press release.

“There’s nothing that I would say is suspicious,” said Pittsburgh Mayor Bill Peduto at the press conference. “I just would say that it hasn’t been properly managed and certainly has never been dealt with in a responsible tone; it was more kick the can down the road.”

Peduto spokesman Tim McNulty said the office welcomes the audit.

“We’re open to help from anybody, when it comes to tackling pension reform,” he said.

The city Department of Finance didn’t return multiple calls for comment from Watchdog.org last week.

While Pittsburgh’s numbers seem high, they’re scant compared to Philadelphia’s $5.3 billion in unfunded pension liabilities and downright meager considering the $47 billion unfunded for state pensions.

There are also strange contrasts in the other direction. Palo Alto Borough, in eastern Pennsylvania, is funded at 3,500 percent. And no, that’s not a decimal-point error, said McAneny.

It’s a result of the pre-1984 state aid formulas, which were based on factors like population and miles of road, instead of need. Aid is now tied to the cost of the plan.

“So the Palo Altos of this world are no longer getting state aid” for this, McAneny said.

According a February auditor general report, nearly 600 municipalities — or 47 percent — of the 1,200 that administer pensions have plans classified as distressed.