ND Supreme Court: Cops Can Violate The 4th Amendment As Long As They Do So Quickly

Yesterday the North Dakota Supreme Court handed down two separate rulings related to the same incident, and it rulings have serious implications for privacy rights and the state of the 4th amendment in North Dakota.

You can read the opinions in State of North Dakota v. Asbach and State of North Dakota v. Walker online.

What happened was that two men from out of state were stopped in their rental car on their way to the State of Washington. They were pulled over for an illegal turn. The officer who pulled them over suspected they may be drug traffickers. During the process of writing them a ticket for the illegal turn he pushed the men to allow him to search their car. He asked the driver repeatedly to search the car, and he refused. The officer then asked the passenger, and he acquiesced.

In the trunk the officer found marijuana. Which, not for nothing, has been mostly legalized in Washington.

At issue before the court was whether or not the officer dragged out the traffic stop in order to pressure the two men for a search. The majority – including Justices Dale Sandstrom, Gerald VandeWalle, and Lisa Fair McEvers – sided with the cops. They said that the cop got the two suspects to acquiesce to a search during the routine duties of a traffic stop, which makes the search and the evidence of crime found during it kosher.

The dissent in the two cases from Justices Carol Kapsner and Daniel Crothers is worth a read, though, because they think the majority got it wrong and I think they’re right. In fact, the headline for this post is from Kapsner’s dissent to the majority opinion is Asbach: “The majority’s holding sets forth a rule that defies our and United States Supreme Court precedent and allows law enforcement to infringe upon individuals’ constitutional rights so long as they do so with haste.”

That’s both true and troubling.

Here’s a summary of the traffic court which the majority quotes from district court proceedings in Asbach:

Officer Bohn did not take any action outside the duties resulting from a valid traffic stop. Officer Bohn approached the vehicle asked for identification and vehicle information from [Asbach and Walker]. He inquired about their destination, the purpose of their trip, and verified their information. He asked Asbach to step out of the vehicle, inquired about their trip and asked for consent to search the vehicle. After being told Asbach could not consent to a search, Officer Bohn approached Walker and inquired about the destination and purpose of the trip before asking Walker for consent to search the vehicle. Walker granted consent. At the time Walker gave Officer Bohn consent to search the vehicle only twelve minutes had passed since the vehicle was stopped. This is not an unreasonable amount of time for an officer conducting a traffic stop to spend verifying the passenger and vehicle information, inquiring about the destination and purpose for the trip, and asking for consent to search the vehicle. Additionally, “[w]hen a motorist gives consent to search his vehicle, he necessarily consents to an extension of the traffic stop while the search is conducted.”

But there’s more to the story. “Law enforcement officers may only extend traffic stops past the point necessary to complete the purpose of the initial stop when they have reasonable and articulable suspicion that criminal activity is afoot,” Kapsner writes in her Asbach dissent. Based on the transcript of testimony in the case from Officer Bohn quoted by Kapsner, it was clear he had no idea if there was a crime to detect. He was, per his own words, on a fishing trip.

Q Okay. So having that knowledge at that time, after you get this story from Mr. Walker, in your mind what criminal activity do you believe that they are committing based on those stories?

A That I don’t know up to that point, and that’s why I did ask for consent to search the vehicle.

Q Okay. But at that point you had no evidence of anything criminal taking place?

A No evidence at that point, no.

. . . .

Q Okay. So when you say you didn’t have any evidence of anything criminal taking place–and you indicated very shortly after that that you asked for consent to search the vehicle; correct?A Correct.

Q What were you searching for?

A It could be a lot of things. It could be anything from contraband to a dead body, I guess. You really don’t know.

“Officer Bohn had a good hunch, but that is all it was,” Kapsner writes. “The majority glosses over the real issue: whether a law enforcement officer, without reasonable and articulable suspicion, may extend a traffic stop to investigate a crime different from the reason for the stop.”

“Officer Bohn pulled Asbach over because he observed Asbach commit an illegal turn. He then questioned Asbach and his passenger about their travel plans,” Kapsner continues. “After hearing their plans, he developed a hunch they might be engaged in drug trafficking. He then extended the stop in order to conduct an investigation into whether the vehicle contained contraband.”

The majority argues that the delay was short – just twelve minutes – but Kapsner argues that any delay at all is unconstitutional.

In the Walker dissent, Kapsner goes into more detail about how Bohn protracted the traffic stop in order to get permission for a search:

In this case, when the driver refused to give police permission to search the vehicle, there was nothing left to be done relating to the stop other than to issue a traffic citation or warning. Officer Bohn had no reason to believe either Walker or the driver was armed and dangerous. The officer had already run a background check on both Walker and the driver and had not found any warrants for either. He had questioned both men regarding where they had come from, where they were going, how they knew each other, and the purpose for their trip. The officer even consulted with a detective to see whether the detective recognized either the driver or Walker as drug traffickers. By the officer’s own admission, quoted in Asbach, none of these investigations and inquiries yielded any information sufficient to give him reasonable suspicion criminal activity was occurring.

What’s more, per Kapsner, the officer gave the two suspects the strong impression that they wouldn’t be allowed to move on until they acquiesced to a search, which is the most damning piece of evidence I think.

“The trial court found that Officer Bohn asked Walker twice if he could search the vehicle and that ‘he told Walker that if he could do a quick search of the vehicle they would be able to get on their way,'” Kapsner writes. Implied, there, is that if Officer Bohn isn’t allowed to do the search they won’t be able to get on their way.

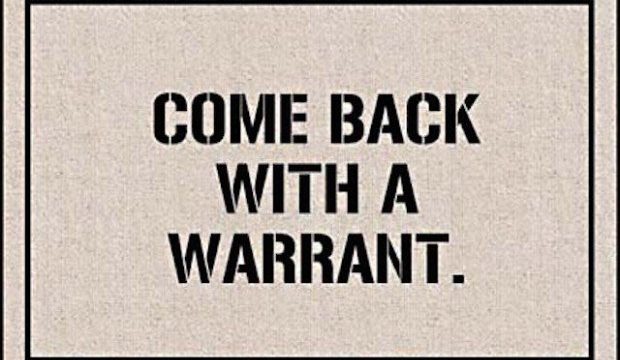

Remember, per the 4th amendment, that absent a warrant you have a right to refuse a search by law enforcement. But do you really have that right if officers lacking evidence to justify a warrant can detain and question you until you give them permission to search?

Some might argue that the two suspects didn’t have to give permission for a search, and that’s true. But then again, should the cops be able to keep asking? And use their power as law enforcement officers pressure a given citizen into giving permission?

If officers are allowed to do that – and these two opinions are giving them that permission – then whither our right to privacy?