Philadelphia economic development program audit finds poor results, bad record keeping

By Eric Boehm | PA Independent

Dotted across Philadelphia are nearly 3,000 acres where businesses get a free pass on paying state and local taxes.

But the investment in special tax breaks is not paying off for the city.

OPPORTUNITY LOST: The audit released last week by the Philadelphia comptroller says the KOZ program isn’t creating the economic benefits it promised.

These select parcels are part of the joint city-state program known as “Keystone Opportunity Zones,” and locating inside one of them will get you a bevy of tax breaks from both levels of government, including reductions in the corporate net income tax, earned income tax, property tax and business gross receipts tax. Projects also receive sales and use tax exemptions for certain purchases.

All those tax breaks are costing taxpayers more than they are worth, but the city doesn’t seem too interested in doing the math, according to an audit from Alan Butkovitz, Philadelphia’s comptroller.

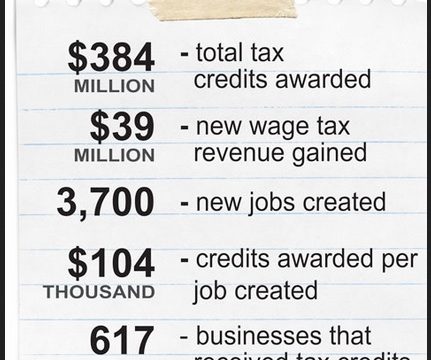

“In short, each new job cost roughly $104,000 in tax credits,” said Butkovitz. “The City has done a poor job at maintaining records and there has been minimal effort to require verifiable annual reporting,”

Butkovitz’ study is the first audit of the KOZ program by Philadelphia officials since its inception in 1998.

When the city first set up the KOZ program, it planned to make up for the tax breaks by applying a new wage tax on city workers and collecting more revenue in the long run because of increased economic activity. Since then, the city has awarded $384 million in tax breaks to 617 businesses, but has recouped only $40 million of those original investments.

At the current pace, it would take 52 years for the city to break even, Butkovitz said.

But the city does not seem interested in measuring the productivity of the program. The audit found that the city Revenue Department and Commerce Department, which oversee the program, do not maintain records necessary to provide adequate oversight of the program.

The Commerce Department shreds new and renewal applications after three years and neither department requires businesses to track job creation or capital investment “in any verifiable form,” the auditors found.

Duane Bumb, deputy director of the city’s Commerce Department, disputes several of the audit’s conclusions. He says the city uses “very different numbers” when it comes to measuring the program’s effectiveness, because the department counts both jobs created and jobs retained — jobs the city would have lost if a company relocated elsewhere.

“There is an assumption that these companies would have built and done whatever they did regardless of whether they got the credit or not,” Bumb said of the comptrollers’ audit.

As for the claims of poor record-keeping? Bumb said the job figures are based on self-reported information from beneficiaries’ applications. The department does not have a way to verify job claims — they don’t have to because the state does not require that for the KOZ program — and the documents are shredded after aggregate totals are sent to the state for tracking.

DANGER ZONES: The 3,000 acres of KOZs in Philadelphia are scattered across the city, but they are concentrated along the rough Market Street neighborhood west of Center City and in several areas in north Philly.

“The comptroller wanted a property-by-property, business-by-business information about the program,” he said. “There isn’t any way for us to go out to a company and say ‘show me all those people.’ I don’t have the staffing resources to do that.”

At the state level, the Department of Community and Economic Development, which oversees the program, provides a report to the Legislature once every four years. But the most recent report, published in 2010, does not verify job creation goals or measure whether the tax incentives awarded were a net gain or loss for the state’s revenue.

For the most part, it’s a promotional brochure that highlights supposed “success stories” with brightly-colored graphics and large photos — pretty much the exact opposite of an audit.

Even without any quantitative assessment, the DCED website touts the KOZ program as “the number one economic development strategy in the nation.”

But companies do have to report job numbers on an annual basis when they apply or re-apply for benefits from DCED, said department spokeswoman Lyndsay Kensinger.

Estimates from DCED for 2012 showed 850 companies in KOZs statewide created more than 15,000 jobs and retained another 9,000. But those figures are not broken down by individual projects.

“KOZ designations encourage development and job creation in areas where little to no tax revenues are currently being generated as well as few to no jobs,” said Kensinger.

But back in Philadelphia, Butkovitz’s team found evidence that the tax credits are given to established companies that already are producing both jobs and tax revenue.

The audit found that finance and real estate companies have received $176 million in KOZ benefits — about 45 percent of the total given away by the city since 1998 — but accounted for only 22 percent of the job growth.

“Our findings are consistent with studies in urban economics, which indicate tax incentive programs such as KOZ are an ineffective tool for enhancing economic growth,” said Butkovitz. “Programs like the KOZ tend to subsidize firms in sectors that are already doing well under local economic conditions.”

A PA Independent investigation into the KOZ program last year found that Urban Outfitters, a national clothing chain with more than 400 locations, got tax breaks from the city and state to finance a $200-million expansion of its Philadelphia headquarters and new distribution center to be built in Lancaster County.

Other KOZ investments seem to pay off, though. The city has spent only $10 million on KOZs for companies working in the retail, utilities and transportation sector, but those have accounted for 70 percent of all job gains in the program.

In some cases, the KOZ parcels are very narrow and rules are written specifically for one business or location. Other times, whole sections of city blocks might be declared a “KOZ” to attract multiple businesses to a certain neighborhood.

And considering Philadelphia’s reputation for high taxes — along with the state’s 9.99 percent corporate net income tax — there should be no surprise why businesses are interested in setting up shop in one of those zones. A business located inside a KOZ has a considerable financial advantage over a competitor located down the block in non-KOZ land.

That’s why it’s “the ultimate tool for picking winners and losers,” said Kevin Shivers, executive director of the Pennsylvania chapter of the National Federation of Independent Businesses.

“Just by virtue of the fact that you are on the wrong side of the street, you are a payer instead of a taker,” Shivers said. “A fairer, simpler tax system would mean we don’t need those structures anymore”

Bumb sees it differently.

“Those sites were undeveloped before the KOZ program,” he says. “Without the tax credits, what was going to happen on that site otherwise? Not much of anything”

Contact Eric Boehm at Eric@PAIndependent.com and follow @PAIndependent on Twitter for more.